The Butterfly

In the preface, Cain said he was originally working on a story about a family that migrates from rural Kentucky to California during the lean years, looking to improve their station in life. But then Steinbeck published his magisterial Grapes of Wrath, so he scrapped the project. As time went on, he collected more and more ideas for other stories. When he finally wrote The Butterfly, he picked and chose various disparate elements from these stories to create one cohesive narrative. All I can say is, if I were Cain I would have been pretty bitter that I had to scrap my original story. Steinbeck's novel has gone down as one of the masterworks of 20th century literature and helped cement him being awarded the Nobel prize, whereas Cain was essentially forced to abandon something that could have been his ticket to greatness and instead create a forgotten novella that will never win anything. Would Cain's Unknown California Novel been in the league of Grapes? We'll never know, but I can't help but think the author must have felt a little resentful that we'd never know.

In the preface, Cain said he was originally working on a story about a family that migrates from rural Kentucky to California during the lean years, looking to improve their station in life. But then Steinbeck published his magisterial Grapes of Wrath, so he scrapped the project. As time went on, he collected more and more ideas for other stories. When he finally wrote The Butterfly, he picked and chose various disparate elements from these stories to create one cohesive narrative. All I can say is, if I were Cain I would have been pretty bitter that I had to scrap my original story. Steinbeck's novel has gone down as one of the masterworks of 20th century literature and helped cement him being awarded the Nobel prize, whereas Cain was essentially forced to abandon something that could have been his ticket to greatness and instead create a forgotten novella that will never win anything. Would Cain's Unknown California Novel been in the league of Grapes? We'll never know, but I can't help but think the author must have felt a little resentful that we'd never know.The first half of this novel is a 2-star affair, the second half 3. It was sufficiently bizarre that I feel it deserves the higher of the two. Incest? Mountain people? Applejack bootlegging? Murder? All in here, folks!

This one is quite a page-turner. That, I expected.

This one is quite a page-turner. That, I expected.What pleasantly surprised me was that Hadley Chase wasn't satisfied stopping there. His characters were archetypical for the genre yet still alive enough to keep my interest. His treatment of a kidnapping victim's fragile mental state, specifically the feelings of worthlessness and self-blame, was particularly refreshing to see in a story that I expected to be nothing but a fun, pulpy romp.

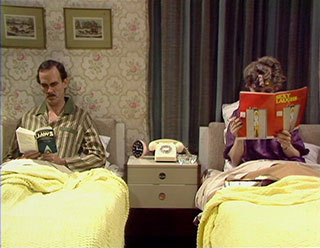

I never would have read this book had I not been watching Fawlty Towers last week and noticed this:

I never would have read this book had I not been watching Fawlty Towers last week and noticed this:

Getting literature recommendations from Basil? Risky, very risky, I know, but I decided it was worth a shot.

I assume a lot of people in the past few decades have come to this book after seeing the massively successful film, but I am not among them. As remarkable as that sounds, yes, I am one of the few dozen people in the industrialized world who has not seen Jaws! I've caught bits and pieces of it on cable TV over the years, but I was never captivated enough to sit through it from start to finish. What I have seen, I don't remember, so I was coming to the novel a tabula rasa.

When I finally picked up the book, I had a preconceived notion. I assumed the movie was a mindless action flick, the characters and their dialogue serving only as spaceholders between big explosions and gratuitous scenes of gore. I was pleasantly surprised that the book really wasn't like that at all, and as a consequence, I'm curious if the movie is. Now I'm not saying this isn't a page-turner, because it certainly is; but it's also a story about a small, East End town (being a native Long Islander myself, I appreciate the publicity), the social dynamic that exists there between the classes, and personal failings of individuals. It was a good effort, but not wholly well-executed. Other than the Chief Brody character, and to a lesser extent his wife, few of the (overwhelmingly) men that peopled the book had much dimension to them.

Lastly, I'll say that I found it hysterical that a significant part of the book dealt with the husband-wife dynamic and how one of these spouses felt unfulfilled because they viewed themselves as from a socially superior caste than their counterpart. When I was watching Fawlty Towers, I assumed they had Basil reading thsi book because it was popular at the time. But now that I've read it and seen how prominent the class issue was, I can't believe the parallel between the character I'm describing from the book and Basil Fawlty's own middle-class haughtiness wasn't intentional.

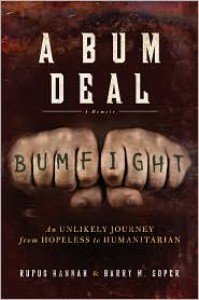

Bum Deal: An Unlikely Journey from Hopeless to Humanitarian

I am absolutely ashamed to say that I owned the Bumfight DVDs when they first came out in the early 2000s. I was in high school, so at least I can blame my poor judgment on immaturity...right?

I am absolutely ashamed to say that I owned the Bumfight DVDs when they first came out in the early 2000s. I was in high school, so at least I can blame my poor judgment on immaturity...right?I'm glad Rufus the "Stunt Bum," has turned his life around. Hopefully I find a copy of this one day, as I'm curious as to just how Rufus got on, and eventually off, the path he was going down.

A fairly straightforward retelling of the life of Alexander from his teen years to his death. All the major events and themes are present: the taming of Bucephalus, the confrontation with a drunk Philip at a bacchanal, his monomania with regards to hunting down and personally destroying Darius, etc. However, as another Goodreads member, FicusFan, so aptly put it in their review, there's a great deal of excision from the Alexander story here, too. "White-wash" may be a bit harsh, and I'm not quite ready to bandy that term yet, but some things are undeniably simplified , incomplete, or just plain omitted.

A fairly straightforward retelling of the life of Alexander from his teen years to his death. All the major events and themes are present: the taming of Bucephalus, the confrontation with a drunk Philip at a bacchanal, his monomania with regards to hunting down and personally destroying Darius, etc. However, as another Goodreads member, FicusFan, so aptly put it in their review, there's a great deal of excision from the Alexander story here, too. "White-wash" may be a bit harsh, and I'm not quite ready to bandy that term yet, but some things are undeniably simplified , incomplete, or just plain omitted.If you've read a book of non-fiction on Alexander, there's not much you're missing from Kazantzakis' novel. The ecstatic prose that I'm used to was absent here, and exchanged for much more subdued, workmanlike language. That could be very much the fault of the translator, however; I believe this is the first translation of hers that I've read.

Far too short. I appreciate the attempt, but it serves as little more than an apéritif. Especially regarding Churchill's pre-WWI life, it proceeds at a breakneck pace. What results is a whir of events and, more egregiously, names that are given little explanation or context.

Far too short. I appreciate the attempt, but it serves as little more than an apéritif. Especially regarding Churchill's pre-WWI life, it proceeds at a breakneck pace. What results is a whir of events and, more egregiously, names that are given little explanation or context.Post-WWI, it gets better. Johnson understandably devotes more attention to the years between the 1910s and 1945. However, this concentration on one period at the sake of another leads to a very unbalanced book. This imbalance was only compounded by Johnson's seeming inability to criticize seriously any of Churchill's decisions. What results is a slim tome more brief hagiography than brief biography, and at times the author's admiration led to him to slip from "breezy historical" to "full-on maudlin" mode.

Johnson did his best to analyze the man and his life's work, and in that analysis, I saw a shockingly familiar parallel to Theodore Roosevelt, who I also recently read a book about ([b:Theodore Rex|40923|Theodore Rex|Edmund Morris|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1320537179s/40923.jpg|210239] by Edmund Morris). Both men were born to prominent families--the Churchills more political and the Roosevelts more commercial; both were highly ambitious and had political minds; both thirsted for action on the battlefield as young men, but once vested with the power they so craved, were responsible with it and did not try to start military conflicts willynilly, were not the blood-crazed belligerents their detractors expected them to be; both were prolific authors and orators of the highest caliber.

I suppose the dictum from the world of physics, that opposite charges attract each other and like ones repel, holds true in the world of human relationships, too, for old Winnie and Teddy apparently did not think too highly of one another. Johnson mentioned in passing that Roosevelt said Churchill was not a gentleman, as evidenced by his decision not to stand when a woman entered the room. A little googling of my own uncovered a letter Teddy Sr. wrote to Teddy Jr. where he called Winston (and his father Randolph) "rather cheap character[s]," that they displayed “levity, lack of sobriety, lack of permanent principle, and an inordinate thirst for that cheap form of admiration which is given to notoriety.” It's no wonder they never invited the other to join them on safari.

Lastly, I thought it odd, and perhaps revealing, that in the "Further Reading" section Johnson called Roy Jenkins' much-maligned [b:Churchill|143628|Churchill|Roy Jenkins|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1309212005s/143628.jpg|138553] "[t]he best one-volume biography I have read." Unless, of course, he was making a joke about the quality of the other one-volume biographies of Churchill...

American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House

A good read, but not a great one.

A good read, but not a great one.First off, it's very short. The life of a man like Jackson is difficult to distill into less than 500 pages. For that reason, this book focuses almost exclusively on his years as President. That brings me to the next strike against it: it glosses over the formation of his character, which in a biography about a man like Andrew Jackson, is practically unforgivable. Thirdly, an unfortunately large portion of the contents revolve around the people around Jackson and their interactions with each other, not Jackson. Of course, these people did not live for Jackson, and as such Jackson is not always the object around which they orbit. But in a book about Jackson, one would think the author could restrict his scope to just those trajectories (especially when there's only a scant 400 some odd pages of content!).

To be fair to Meacham, however, he did make this clear in the prologue when he said the following: "This book is not a history of the Age of Jackson but a portrait of the man and of his complex relationships with the intimate circle that surrounded him as he transformed the presidency." While I appreciate the caveat, it just left me wanting more. He acknowledges he hasn't written a political biography, yet the last ~150-200 pages were pretty much focused just on politics. (Those pages also happened to be the best of the book.) For that reason, I don't think he was even consistent with his purpose. While a large swath of the book was indeed a "portrait of the man and of his complex relationships," a roughly equally large portion felt like a standard political biography, which I would have preferred.

Overall, it was enjoyable and I appreciate that it gave me a glimpse, albeit a narrow one, into who Jackson was. Meacham writes well and is generous with quoting directly those whom he writes about. The book's greatest strength, however, is that it whet my appetite to learn more about the 7th President.. I'll be doing my research into whose biography to read next. Preliminary choices are Brand's single volume or Remini's trilogy.

If what Elliott House has written is accurate, it's a miracle that Saudi Arabia has managed to prevent itself from descending into chaos by now. The divisions are manifold: traditionalists vs modernizers, religious fundamentalists vs. secularists, men vs. women, the old vs. the young, Saudis vs. foreigners, the rich vs. the poor, the al Saud vs. everyone else...ad infinitum.

If what Elliott House has written is accurate, it's a miracle that Saudi Arabia has managed to prevent itself from descending into chaos by now. The divisions are manifold: traditionalists vs modernizers, religious fundamentalists vs. secularists, men vs. women, the old vs. the young, Saudis vs. foreigners, the rich vs. the poor, the al Saud vs. everyone else...ad infinitum.

Theodore Rex

I am not usually a reader of biographies, and certainly not a ravenous one. But when it comes to Edmund Morris' works, I break character. Like The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt before it, I devoured Theodore Rex. Though I had a false start--I tried to read it immediately after the magisterial first volume of the TR trilogy and burned out about a third of the way through--once I put some distance between myself and The Rise, I was captivated all over again.

I am not usually a reader of biographies, and certainly not a ravenous one. But when it comes to Edmund Morris' works, I break character. Like The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt before it, I devoured Theodore Rex. Though I had a false start--I tried to read it immediately after the magisterial first volume of the TR trilogy and burned out about a third of the way through--once I put some distance between myself and The Rise, I was captivated all over again.Morris has such a (seemingly) effortless talent for writing. He is literary, but to my untrained eye, style precipitated no sacrifice in scholarship. Meticulously researched and rapturously written, Morris is obviously a man deeply fascinated by Roosevelt. Much to his credit, though, he presents Teddy as he sees him, which is thankfully not free from his many warts.

An admiring biography, but not a hagiography.

A charming little story. Any attempts to summarize it would do it injustice, would make it sound like a trifle. Its simplicitly, however, is a strength. Oz writes in wonderful prose, and the story is just ambiguous enough to adumbrate a number of possible interpretations, likely all and none correct.

A charming little story. Any attempts to summarize it would do it injustice, would make it sound like a trifle. Its simplicitly, however, is a strength. Oz writes in wonderful prose, and the story is just ambiguous enough to adumbrate a number of possible interpretations, likely all and none correct.

Wizard's First Rule (Sword of Truth, #1)

This was one of my first forays into the fantasy genre (despite Goodkind vehemently denying that he's a fantasist). The only other fantasy novels I've read are both by J.R.R. Tolkien, and even that was years ago. Consequently, I'm not sure where Goodkind ranks in the pantheon os bestselling fantasy authors. All I can say is that his prose was uninspired, and as the book wore on, the storyline became more beleaguered by dei ex machina. What I mean by the latter specifically is the previously unmentioned qualifications he put on certain relationships. For example, an X can kill a Y and a Z--unless, of course, Y is so-and-so, and Z is such-and-such. In those two cases, X can't kill them because [insert justification necessary so as to not screw up his carefully lain plans]."

This was one of my first forays into the fantasy genre (despite Goodkind vehemently denying that he's a fantasist). The only other fantasy novels I've read are both by J.R.R. Tolkien, and even that was years ago. Consequently, I'm not sure where Goodkind ranks in the pantheon os bestselling fantasy authors. All I can say is that his prose was uninspired, and as the book wore on, the storyline became more beleaguered by dei ex machina. What I mean by the latter specifically is the previously unmentioned qualifications he put on certain relationships. For example, an X can kill a Y and a Z--unless, of course, Y is so-and-so, and Z is such-and-such. In those two cases, X can't kill them because [insert justification necessary so as to not screw up his carefully lain plans]."Maybe two stars is overly harsh, but the last two- to three-hundred pages of this one became a real slog. Coupled with the (at times) silly characterizations of "the bad guys," and the disturbingly gratuitous torture-porn scenes, I can't go higher.

Always Right

Good, but too brief to be of any great use. Contrary to some of these other reviews, I thought Ferguson was fair in addressing both the good and the bad of Thatcherism (though he certainly found it to contain more of the former than latter).

Good, but too brief to be of any great use. Contrary to some of these other reviews, I thought Ferguson was fair in addressing both the good and the bad of Thatcherism (though he certainly found it to contain more of the former than latter).

The Mystery Of Capital Why Capitalism Succeeds In The West And Fails Everywhere Else

De Soto puts forth a compelling thesis and has a wonderful ability to explain himself to anyone of at least average intelligence. However, as a consequence, the book mainly focuses on the "big picture" and details about policy and implementation are scant. He tends to repeat himself very frequently as well, which leaves one feeling that he could have accomplished his task in half the number of pages.

De Soto puts forth a compelling thesis and has a wonderful ability to explain himself to anyone of at least average intelligence. However, as a consequence, the book mainly focuses on the "big picture" and details about policy and implementation are scant. He tends to repeat himself very frequently as well, which leaves one feeling that he could have accomplished his task in half the number of pages.

Five stars for the ideas, but considerably less for the collection compiled here by Haddad. I say that because they vary in quality, from pithy and impassioned to drawn out and repetitive. This would serve as a decent primer for those unfamiliar with Ron Paul who want to learn what he's about, as essentially all of his major beliefs are outlined by these quotes. But for someone who is already a Paulist, there's little you'll get out of it if you read it cover to cover. Maybe if you want to keep it around as a coffee table book, it will serve that purpose well.

Five stars for the ideas, but considerably less for the collection compiled here by Haddad. I say that because they vary in quality, from pithy and impassioned to drawn out and repetitive. This would serve as a decent primer for those unfamiliar with Ron Paul who want to learn what he's about, as essentially all of his major beliefs are outlined by these quotes. But for someone who is already a Paulist, there's little you'll get out of it if you read it cover to cover. Maybe if you want to keep it around as a coffee table book, it will serve that purpose well.

Frederic Bastiat : A Man Alone

Bastiat truly was a man alone. Both his clear-headed thought and his indefatigable desire to bring liberty to the people of France, and eventually the world, were eminently admirable qualities. Roche's book is more of a biography of ideas and a history of the eponymous hero's socio-political milieu than a traditional biography that focuses on life events. The vast majority of Bastiat's life was supremely uneventful and of little interest to any but the most obsessive types. During his last five years, however, he went through an incredibly fruitful period and produced much of his works of genius that we are left with today. It is understandably this short period of time that Roche focuses on most.

Bastiat truly was a man alone. Both his clear-headed thought and his indefatigable desire to bring liberty to the people of France, and eventually the world, were eminently admirable qualities. Roche's book is more of a biography of ideas and a history of the eponymous hero's socio-political milieu than a traditional biography that focuses on life events. The vast majority of Bastiat's life was supremely uneventful and of little interest to any but the most obsessive types. During his last five years, however, he went through an incredibly fruitful period and produced much of his works of genius that we are left with today. It is understandably this short period of time that Roche focuses on most.

I know that one common criticism of Anthem is that it very closely resembles Zamyatin's We. That may be so, but since I haven't read the latter, I can't comment, nor fault Rand, for any supposed similarities between the two. I can only judge this book on its perceived merits.

I know that one common criticism of Anthem is that it very closely resembles Zamyatin's We. That may be so, but since I haven't read the latter, I can't comment, nor fault Rand, for any supposed similarities between the two. I can only judge this book on its perceived merits.Another criticism seems to be that it contains absurdly one-dimensional characters. I agree, they are not multi-dimensional. But I'd respond, isn't that the intent? Certainly unique individuals with complex personalities wouldn't exist in the soul-crushing, repressive dystopia that we find in Anthem. So I can't fault Rand for one-dimensional characters, either; that, I believe, was deliberate and served to reinforce the theme of the story.

I know very little about Rand's philosophy--just what has been filtered down to me third-hand--and therefore I'm fairly free from bias when it comes to her writing. I possess neither the bitter hatred, nor the sycophantic obsession, that some harbor for her. I thought Anthem was quite good, and that is that. Her prose, while not coruscating, was very readable and enjoyable. Like many other 20th century dystopian novels, this one goes the conventional "celebrate the individual" route. I will say, however, that in the 11th chapter, Rand probably went a little bit farther than others in her celebration of the individual. She is adulatory nearly to the point of obnoxiousness.

Still, overall, for all its faults, I had a good time reading this slim little volume, and can't say I'm hostile to the overaching theme of the story. Nor am I hostile to the idea of reading more of her work, namely Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead. Perhaps it will make a detractor out of me, or perhaps it will make a new fan. Either way, I'll try to form my opinions from the books themselves, not the (I suspect agenda-based) interpretations of others.